- Critical Question #1: Are publishers using gendered art to sell your books?

As Flood points out, Maureen Johnson focuses in her article on having us examine our novels’ cover art. It’s a fun challenge, but responses to Johnson’s and Flood’s articles show everyone taking the argument seriously. Here’s Johnson’s challenge:

[T]ake a well-known book [and] [i]magine that book was written by an author of the opposite gender. Or a gender queer author. Imagine all the things you think of when you think girl book or boy book or genderless book.

As Flood further discusses, Johnson isn’t judging these categories, whether they’re “right” or not, but says Flood, “Make no mistake, they’re there.”

- Critical Question #2: Do you use gender neutral pseudonyms?

Flood also questions writers who change their name to avoid gender bias. I think immediately of Nora Roberts, who writes suspense as J.D. Robb. Does she do so to net an audience of readers different than that associated with her widely recognized romance novels? Does this audience include males who read the gender neutral J.D. Robb, but who might not read Nora’s romance? Interestingly, Flood mentions–as an aside–suspense novels written by males and which include the “obligatory sex scene” to appeal to female readers.

- Taking up Johnson’s Challenge: A Brief Study of Zola’s Nana and It’s Gender Biased Cover Art

Why should we care what publishers (or illustrators if we’re self publishing) are doing with our novels’ cover art?

We should care because cover art reflects the culture in which we write, and it reflects our attitude as writers toward it. Covers are visual maps others will use to one day navigate and read our cultural history and to discern how we as authors responded–bravely, boldy, cavalierly or indifferently.

- Critical Point #1: Nana is anything but a girly romance.

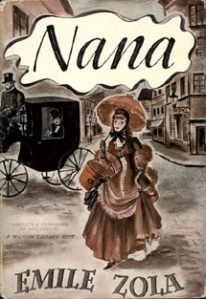

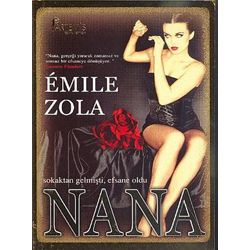

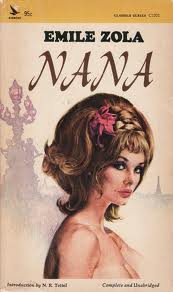

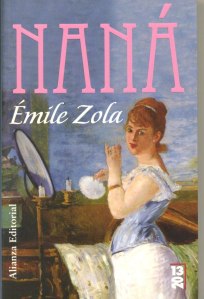

As our way in to Johnson’s challenge, I selected Emil Zola’s Nana, a choice which helps me support–and expand–Johnson’s argument. I look at the treatment by publishers of cover art for Nana. What is the art saying about publishers’ response to each cultural period?

Nana Coupeau, the protagonist of Nana, rises from street walker to a kept cocotte. After destroying the careers of several prominent men who can’t resist her, she dies. Sounds like a girly romance to me, you say. But Nana is no more a girly romance than Anais Nin is a porn writer. Nana is literature–super literary. The novel’s a metaphor for France’s decaying Second Empire. The ninth installment of the twenty-volume Les Rougon-Macquart series, Nana is a realistic novel, written in 1890 to chronicle the history of a family under the Second Empire (Le Second Empire Francais) of Emperor Napoleon III.

Yet looking at the covers, you’d think Nana was precisely a girly romance, or in some instances even worse, more like soft porn.

- Critical Point #2: There’s a tradeoff between Nana’s content and its gendered covers.

How do Nana’s covers reflect on the various cultural periods since the novel’s first publication?

The first edition’s cover is available only in online curated museums, so I cannot evaluate it. I’ve learned, however, that the original cover was illustrated by Albert Lindegger, a Swiss painter, political satirist and caricaturist, who spoke out frequently about Nazi Germany. I thus doubt the cover resembles a girly romance novel’s, not as you and I envision them. Unfortunately, many of Nana’s covers do. So how did this realistic and politically intense novel end up perceived–if you judge it by its many gendered covers–as a girly romance?

Look at a few samples of covers from various periods (below). What do you think these covers say about the cultural period, about Nana the novel, and about the publishers’ intent?

Take The Challenge: Examine Your Choice of Cover Art.

Flood and Johnson leave resolving the argument about what publishers are doing up to us. Yet they provoke us to deep thought. Our cover art choices linger with our reputations as writers and cultural commentators forever. I doubt Zola would enjoy having Nana described as a girly romance?

So here’s your challenge:

- Consider if your novels’ covers reflect gender bias. If you think that’s something publishers will do with your future books, what can you do?

- If you’ve gone indie, make good decisions about cover art.

- Think about how your novels’ covers reflect on our culture, and how they could in future end up like Zola’s Nana. How, exactly, do you hope your novels will be perceived in the future?

Flood, Alison. www.guardian.co.uk/books/2013/may/09/coverflip-maureen-johnson-gendered-books.

Johnson, Maureen. www.huffingtonpost.com/maureen-johnson/gender-coverup_b_3231484.html.

Special thanks to www.debragaskillnovels.com for pointing out Flood’s article.

Copyright 2013. Mary H. McFarland. All rights reserved. But you may freely plagiarize.